I know I do a lot of pop-psych bashing here on Unpopular Psychology. I wish I didn’t have to do it, at least not so much of it but I see these folks everywhere spraying pop-psych nonsense like an old air freshener that you know smells bad but still inhale just because it’s labelled ‘freshener’. Pop-psych is omnipresent. They flood my Instagram. They flood my Linkedin. They flood the internet. It’s too much really, you know how I feel about this stuff. So these days, my main activity is to plant myself firmly in a corner of my room and spread Un-Popularity to balance things out a little bit. Join me, will you?

I. Okay, so what are we going to take on pop-psych about today?

Nothing. Today, we are going to understand why popular psychology stays popular. So many of the things we spoke about since the launch of Unpopular Psychology (uselessness of too much processing, usefulness of guilt, awesomeness of productivity, dangers of empathy) are not brand new topics. I’m not the first one on planet Earth to dispute popular psychology or display an affinity towards critical inquiry. Most of my articles are a combination of curated research+original contributions. I don’t have privileged access to any erudite corners of the internet. Why don’t the popular psychology folks find these facts then? Wouldn’t they like to know if the stuff they are propagating is actually true? Who is blindfolding them? What’s the blindfold made of?

II. The mother of all cognitive biases

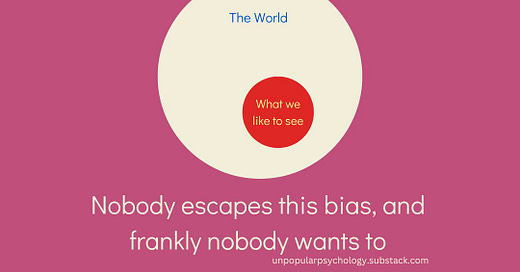

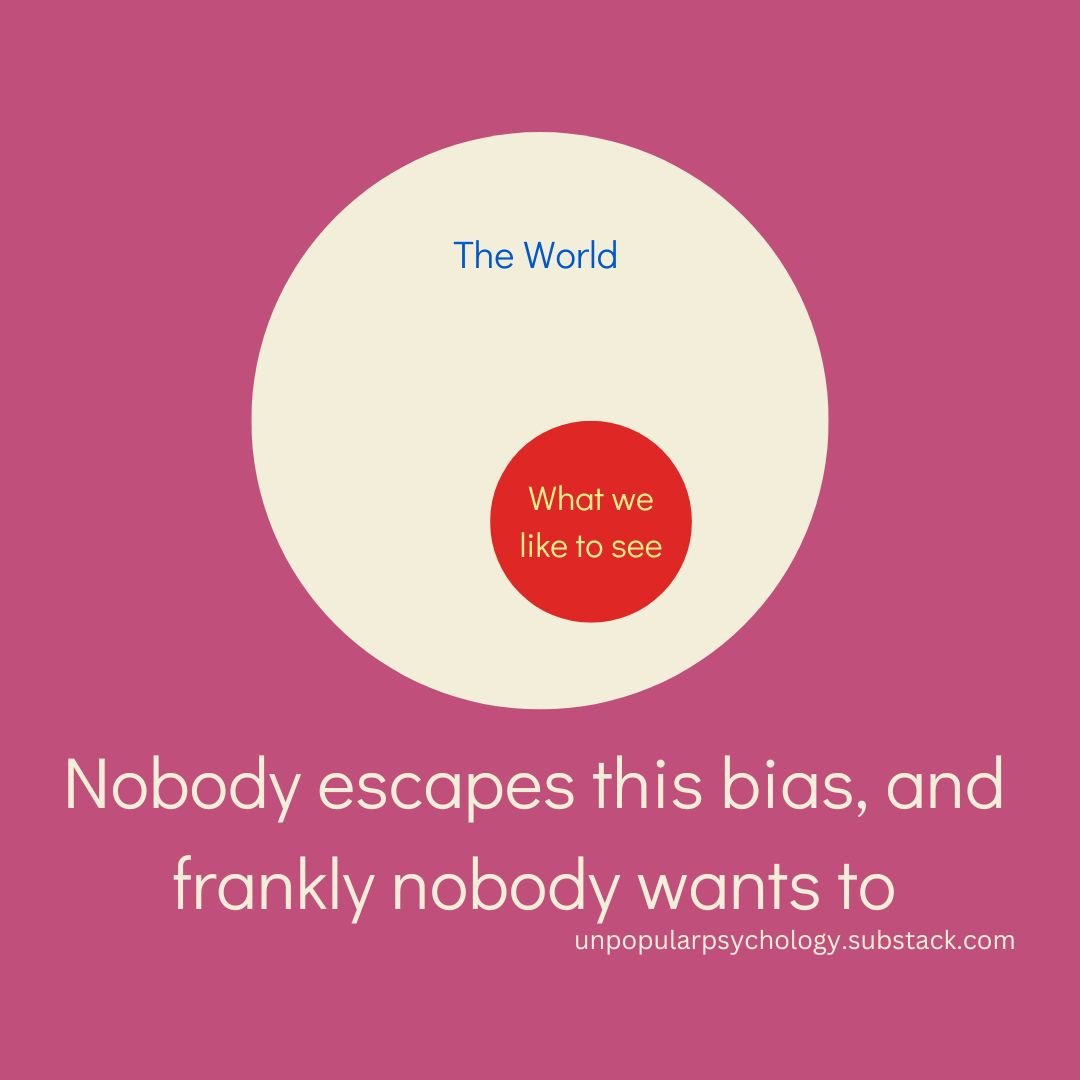

Have you heard of confirmation bias? Some of you may know what it means, others may pretend like they know what it means, a few others may not care what it means. To groups 1 and 2, confirmation bias is the tendency that we humans have to be partial to information that agrees with our existing beliefs. How convenient!

Basically what this means is that out of all the facts that are available in the world, we pick out the ones that suit us and our beliefs the best. If you think that climate change is the biggest crisis of our times, then your ears perk up every time you hear about a wildfire. If you think that climate change is a hoax, then Greta Thunberg just needed an excuse to get out of school. If you revere the Dalai Lama, no controversy can shake you off your faith in His Holiness. If you think the Dalai Lama is overhyped, then you are not surprised by any controversy. If you look up to Karl Marx, you look down on Jeff Bezos. If your husband, who you believe is faithful, gets caught cheating, you are confident that he was lured into the act. If you didn’t get the promotion you thought you deserved, your boss must be to blame. If you think Rahul Gandhi is great, then his admission to Harvard makes sense. If you think Rahul Gandhi is dumb, Harvard must have gone by his family’s legacy. If you’re scared of dogs, every dog out there is waiting to get you. If you love dogs, all dog-biting stories sound made up. If you are a vegan, you will always be evidence-ready to argue with the meat eaters. If you eat meat, you want vegans to stop eating avocados immediately. If you believe that women are bad drivers, you will see terrible women drivers everywhere. If you’re a writer who is not doing well, you will see everybody switching to podcasts. If you’re a struggling podcaster, you’ll see everybody writing a book. And if you’re an Unpopular Psychology practitioner like me, you’ll see only pop-psych nonsense everywhere.

Confirmation bias makes our brain interpret information (both old and new) in ways that fit with its existing beliefs. For example, you may view anything that a Yale alum says as brilliant if you have a pre-existing belief that all people who go to Ivy League universities are brilliant. Confirmation bias also makes us favour information that fits with our world views. If you’re a Republican, you may selectively choose to highlight data that paint the Democrats in a bad light. Other times, confirmation bias makes us search for evidence that validates our beliefs. If you believe that homoeopathy works, you may go out of your way to collect proof that supports homoeopathy while ignoring all evidence against it.

Confirmation bias is such a hard bias to catch because it is context-agnostic. You could be doing it right now. You could be agreeing vehemently with some parts of this article while reading over the sections that don’t sit well with you. I could be doing it right now. I could be emphasising more on points that I’ve always believed to be true and not giving enough space to the ones that I don’t care much for.

III. Why do our brains make us conform to our biases? Is there an evolutionary reason?

Our brains like it easy. Remember the time we tried to understand why we procrastinate? When given a choice, our brain always chooses the low effort-instant gratification route. It’s easier to think that Elon Musk is the main reason for the sorry state of our world than to reckon with the role that we may have to play in it. It’s easier to buy into propaganda than question it. It’s easier to justify your Youtube Premium purchase as an educational investment than admit that you don’t like seeing ads when you’re busy procrastinating. Our brain doesn’t like to be challenged. So it goes out of its way to avoid it (challenge avoidance), by seeking out information that fits in with what it already thinks of as the truth.

That we live in a highly complex world only makes our brains succumb to confirmation bias more strongly. We are inundated with news, social media, advertisements, propaganda, Whatsapp forwards, our own experience, religious teachings, moral policing, there’s just so much thrown at us at any point in time. This makes the information territory overwhelming, ambiguous and murky to navigate. And we hate ambiguity. We don’t like to not know. It’s the reason why we assume that our partner is upset at us if they seem more silent than usual. It’s the reason why we like to be friends with people who agree with us politically. Our hate for ambiguity is why we claim knowledge of Bush’s involvement in 9/11 and behind-the-scenes of NASA’s orchestration of the moon landing. It’s also why creationists’ theory ruled for so long. Before Darwin, Einstein, Hawking and black holes, how else could we explain the existence of this marvellous universe? We are (understandably) averse to any kind of cognitive dissonance. We don’t want our belief systems to be messed with. We don’t like confusion. We want neither people nor evidence coming in and telling us that we’re wrong. We want reinforcement, consistency, agreement, praise and everything else that makes us feel good about who we are and what we say. Why weaken our worldview when we can strengthen it?

Another reason why our brains haven’t gotten rid of confirmation bias is because of the role that it plays in social adaptation. Imagine not being able to present a united front as a couple, or not being able to nod vigorously to your boss’ arguments at a board meeting or having to leave your best friends group. Confirmation bias helps us stay glued to the communities we belong to or choose to be part of.

Studies have also shown that we get a rush of dopamine which is a molecule responsible for motivation, feeling good etc. every time we are agreed with or are proven right. This makes sense. When being right feels so good, why would we want to feel like we’re wrong (even if we are)?

Confirmation bias also helps us win arguments and maintain our social standing. This especially was of great use when we lived as hunter-gatherers. We wanted to protect our tribes from being taken advantage of, doing disproportionate amounts of work or being manipulated by other tribes. Cognitive scientists Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber in their book The Enigma of Reason posit that this could be why rational thinking abilities have not evolved to help us tackle complex issues such as fake news and propaganda. Reason, back in the day, was mostly used to minimise risk to survival and now times have changed too fast for the function to catch up. All this to say that even highly rational thinkers can fall prey to the traps set by mother confirmation bias.

IV. How do we decide which biases to conform to?

The literature is not super clear on this but there are some interesting hypotheses that I came across both during research and from conversations:

We conform to the biases that hold the right incentives e.g. If you are a religious priest, it works better for you if you believe in creationism. To understand evolution or entertain the idea of atheism would be to begin digging your own grave.

We conform to the biases that signal status e.g. There was a time when supporting homosexuality or coming out as gay had strong implications for life and career (remember what happened to DeGeneres in 1997?). Thankfully, times have changed. Today homophobia can lead to much social isolation and rejection while being an LGBTQIA+ ally signals progressive thinking.

We conform to biases that our friends/family/bosses conform to e.g. If your husband is an anti-vaxxer, how strong a stand against anti-vaxxers will you be even comfortable taking?

V. How confirmation bias interacts with pop-psych (and everything else)

Firstly, pop-psych falls into the trap which gives practitioners conviction: Think of any pop-psych influencer that you know of. You could have seen them on Instagram, you might know a few in real life, or you might be one yourself (which is cool, welcome to unpopular psych). Pop-psych guys talk with so much passion and conviction. And most likely, they’re not pretending at all. They might genuinely believe what they are promoting in the name of good mental health. And because they’re convinced of what they’re saying, the conviction often comes through. For example, an anti-work, anti-productivity person might probably know all of 50 real, severe cases of burnt out employees. Since they are already anti-work, they will hold on to these few cases to strengthen their belief that productivity is terrible for mental health. They’ll direct you to stop feeling bad about not getting stuff done. It might not occur to them to look up if their understanding of productivity matches the real meaning of the term or challenge popular notions of our times e.g. we are working a lot more than our forefathers (no, we’re not).

Followed by influencing: Once they’re convinced, then they are on a mission to convince everybody else. Because none of us like ambiguity, remember? If all of us think and feel and talk the same way, nothing like it right? The world then will be a true haven for pop-psych and conspiratorial theorists to float without obstructions.

Often pop-psychology leverages its lived experience to make you generalise: Overgeneralization is rampant, we all do it. One very common mistake that people make is to use their personal experience to make broad claims. “I had a terrible experience with that event management company, don’t book them.”, “My mother hit me a lot when I was a kid and I turned out fine, I don’t know why parents nowadays hesitate to use the stick.” or “Everybody I’ve met at their office is so approachable and nice, I don’t know why you’re against this party.” Pop-psych practitioners too, use their lived experience to make you believe e.g. “Feeling guilty has never helped me with anything, I don’t think that it’ll do you any good either”. Because after all, who is anybody to deny another person their experience?

Pop-psychers aim to please: We like to be liked. And we like people who reply with yeses. If I think that India is a dangerous place, wouldn’t I appreciate and thank the person who keeps me posted of all the recent crimes in the country? If I think that Musk is a terrible human being, wouldn’t I appreciate learning that his ancestors owned slaves? If I am feeling demotivated at work, wouldn’t I appreciate a communist telling me that it’s entirely my employer's fault? If I’m poor, wouldn’t I appreciate someone telling me that the government is to blame?

They leverage empathy: Last week’s post went into great detail of how pop-psych practitioners do this, so I’m not going to do it again here.

Pop-psych appeals to your emotional brain: An oversimplified but still useful for our purpose diagram of the brain will show you that the human brain has 3 separate yet interconnected parts - forebrain, midbrain and hindbrain. The hindbrain developed first and is responsible for helping us breathe, sleep etc., midbrain came second and is responsible for helping us feel, emote etc., forebrain came last and is responsible for helping us think, question etc. Our emotional brain is super powerful. Aside from the fact that it is the older, more senior part of the brain, it has an involuntary and impulsive personality. When the emotional brain and logical brain come head-to-head, the logical brain doesn’t stand a chance. While this helps with general survival, it can also lead us to doing stupid things sometimes e.g. spending $5000 on a handbag because our colleague described our current handbag as cheap-looking. Pop-psych practitioners appeal to our emotional brain because they know that’s when they have the highest chance of conversion. They know what you want to hear, they know how to invoke anger in you, they know how to make you feel sad, pop-psych is the algorithm that we all need to be wary of.

VI. The guy confirmation bias is sleeping with

Availability heuristics. Availability heuristics is eerily similar to confirmation bias but there's a tiny, significant distinction. Availability heuristics refers to our tendency to make decisions primarily based on the information we are able to recall.

Consider this question: Which do you think is more dangerous - travelling by air or road? You might say flying is more dangerous if you are able to recall 9/11 or MH370 incidents faster, or if you have a fear of flying. If you recently had a narrow escape from a car accident, you may give a different answer.

You may choose to avoid eating from a certain restaurant because you recently got food poisoning from a meal there. You may have completed 10000 safe trips on Uber but a singular bad experience with a driver will leave a stronger imprint, and lead you to rate the company low on safety.

Factfulness by Hans Rosling is a fantastic resource to test how much you fall for availability and other cognitive biases on a daily basis. Other books/articles to read if you’d like to learn more about this topic are here, here, here and here.

Pop-psych practitioners tap into these mental shortcuts to get us to sway in their direction. For example, they’ll tell you that all psychiatric medication is BS because of the recent UCL study that delinked low serotonin and depression. That one of the ways science advances is also by disproving past theories is something they might “accidentally'' forget to mention.

VII. Other mini dons that pop-psych has on speed dial

Black and white thinking, Mind reading, Overgeneralization, Suggestibility, Framing Effect.

I may have detailed posts coming out on these mini dons in the future but for now, what we need to remember is that pop-psych is itself a victim of these mini dons’ activities (along with the big dons i.e., confirmation and availability biases) or the practitioners leverage it to become or remain popular.

VIII. How to pull a fast one on pop-psych? Is it even possible?

It’s tough, but not impossible. Some tips to get you started:

Identify people who appeal to your rational brain instead of emotions (can be difficult, I know, but try): We are highly emotional beings. We eat, pray and love while riding high on emotions. We respect, hate, worship, detest, reject, fear and value things and people based on what is trending. But every now and then, you will come across groups and people that rank low on trait neuroticism and high on critical thinking and logical reasoning. Try and make friends with them too (don’t have to ditch your drama-ridden friends or anything). Not that they get it all right a 100% of the time but they get it right more times than most others.

Be your own critic: Find counterexamples to your own examples. If you truly believe that the climate crisis is the biggest risk of our times, find evidence that counter it. Evaluate the merit of those claims as a way to truly validate your thinking on the topic. Or if you feel that your city is really unsafe for women, dig up data that challenge that feeling. If you don’t find any, that means you were probably right which is great. Or sometimes, the exercise itself will help you realise there is no reliable data on women safety for your city.

Be a skeptic: Even as you are reading this article, reflect on the parts that you easily agreed with. Which parts put you in doubt? Were you able to spot areas where my confirmation bias tendencies showed up? Which parts of this article seem incorrect? Why?

Follow people whose work completely disagrees with your ideologies: If you are a serial monogamist, explore literature on polyamory even if with a more intellectual, less personal lens. If you’re a liberal, attempt to understand a conservative’s point of view even if you end up disagreeing with it for a second time. If you’re a vegan, research the potential benefits of non-vegetarianism.

Work through the implications of your beliefs: If you feel that the rich should be forced to commit more money to philanthropy, think through the negative consequences too of putting a policy like that in place. If you feel that the government should be given more power, search our world’s history or simulate mini experiments to see if it will actually lead to the effects that you desire.

Read more unpopular psychology :P

IX. Fork in the road

I don’t think pop-psych means ill. They just mostly fail at getting better of their cognitive biases. We all have an inherent craving for validation and agreement, they are no different. The problem emerges when confirmation bias gains strength by numbers. When we get caught up in Left vs Right politics, Pro-life vs Pro-Choice, Capitalism vs Communism, Religion vs Science, and of course Popular Psych vs Scientific Psych (aka Unpopular Psych), we get busy defending our ingroups and emulate groupthink, groupspeak, groupdo.

A lot of this behaviour unfortunately happens unconsciously. When our own brain is against the pursuit of truth, that really throws a spanner in the works. But that does not mean that we should give up. The progress of our species has been made possible because of our ability to get the better of our biases, both by leveraging them when they are helpful and circumventing them when they are not. A helpful step towards this is cultivating awareness that we can be wrong and then when we turn out to be actually wrong, to accept it and move towards being less wrong.

So here we are, once again, at a fork in the road. One road boasts of a familiar, agreeable path filled with lots of validation and a 100% clarity; no major challenges or obstacles. The other path, the road less taken, is filled with uncertain potholes, circuitous side routes, plenty of grey patches, disagreements and criticising bystanders. Only one of them, though, promises to help us arrive at the correct destination.

That’s it.

Want to low-key thank me for my writing? You can like, share, comment, and subscribe.

Want to middle-key thank me for my writing? Buy me a coffee (I’m going to use it for chai, sorry).

Want to high-key thank me for my writing? You can give a gift subscription (involves monies).

Great post, both clever and useful. Thanks for this.